Populism and Big Money’s Attack on India’s Post-Emergency Social Contract

Hidden linkages that harm the Indian Democracy and a hopeful way forward

Stills from the Emergency. George Fernandes in chains (Left). Supporters shielding JP Narayan from a Lathi Charge in 1975 (Right)

Credits: Left – Hindu Archives (Frontline) | Right – Raghu Rai (Instagram)

“If you really care for freedom, liberty, There cannot be any democracy or liberal institution without politics. The only true antidote to the perversions of politics is more politics and better politics. Not negation of politics.” – Jayaprakash Narayan

The biggest positive consequence of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s Emergency imposed on June 26th, 1975, was the silent rejuvenation of social contract between the institutions of policy and polity and the people of India. This was following the emergency which derailed our democracy by killing the Constitution and dismissing rights including those to criticise and mobilise. Lasting for two years before a grassroots mass movement led by a Leftist Leader, Jayaprakash Narayan, who was bestowed the title of People’s Leader (Lok Nayak - if you ever come across a building or statue with this name, you know who the great man was).

50 years since, we are now in an age of impunity and with it came the rise of populist leaders who are favoured by capitalists. This is not just an Indian phenomenon alone, quite global. Neither this age nor the populists and capitalists of it are a new phenomenon in the history of our world. Despite knowing this and having a belief in the people who will not stop rising against power through any means necessary, I am scared for our democracy. We may not have a Mrs. Gandhi or the Mr. Trump who takes a bazooka to the Constitution in India anymore and yet, respectively, but we have hollowing parties, weakening institutions and a rapidly evolving society who might realise the democracy’s death by a thousand cuts a little too late. The times when democracy was subverted by coups is gone - the approach today is a lot more subtle (Levitsky et al, 2018).

Election manipulation was a frontier cause for decline in freedom scores of 26 countries worldwide (Freedom House, 2024). In sharp contrast, India has been relatively successful in ensuring transparency and accountability across multiple state elections and national elections. This phenomenon, especially with political financing, the colosseum of capitalists, has always been dependant on the power and presence of veto players* (Chang, 2008). Post-emergency social contract reinforced the Indian people, state governments, political parties, free media and the judiciary as veto players of the polity. This social contract, to my mind, is under threat from populists and capitalists who wish to centralise power and profit off that power respectively.

Do I have your attention?

*Veto players are stakeholders that hold the power to reject an action that a player takes.

*Social contract is an implicit agreement between members of society to cooperate with citizens giving up certain rights and accept an authority to protect their rights

Choosing between Political Parties and Constituencies

The Electoral Bonds Scheme (EBS), introduced in 2017, provided an uncontrolled channel to finance political parties. This policy provided the State Bank of India (SBI) with the power to issue bonds to corporations and individuals that can help them donate to political parties of their choice ‘anonymously’. In February 2024, the 50th Chief Justice of India – D.Y. Chandrachud passed the judgement that declared EBS unconstitutional. The Supreme Court (SC) held that the EBS violated our fundamental rights and brought an immediate stop to its implementation including the amendments to three other legislations (Bhaumik, 2024).

“Information about funding of political parties is essential for the effective exercise of the choice of voting” – from the EBS judgement by D.Y Chandrachud, former Chief Justice of India.

EBS obliterated barriers on political financing and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) gained 54% of its reported income from this channel in 2023-24, seven times more than its closest political rival, the Indian National Congress (INC). The law removed the legal obligation on corporations to disclose donations as well as the pre-existing financial caps on parties to accept donations. Before the passage of this legislation, companies could only donate up to 7.5 percent of three years of the company’s net profits. Under the guise of ensuring donor privacy, EBS ensured that the details of donations are kept confidential unless ordered by the court in a criminal case. This placed the details of donations and donors beyond the ambit of the Right to Information (RTI), making these details opaque to people, taking away transparency of party’s funders and thereby people’s right to that information (Vaishnav, 2024).

Enough about the bonds that went away but were not replaced by any other transparent mechanism, despite the government’s promise (are you really surprised they flaked on it too?). In addition to cash still being used to attempt to manipulate elections as evidenced by crores of rupees being seized before the 2024 elections (PIB, 2024), that remains just the tip of the iceberg. While elections continue to get more expensive, consistently winning narrative battles, firing up personalist popularity nationally and satiating people’s growing information appetite on social media platforms have become impossible without the top 1% and party machinery that functions as a corporation within itself. Almost all major political parties in India today do this and most of the backing for these activities is beyond the traditional political financing - there’s something more sinister at play here.

Beyond the direct political financing of parties, the once-riotous media landscape has started to become dominated and tamed by India’s very own Robber Barons like Mr. Gautam Adani, who got a controlling stake in NDTV recently and Mr. Mukesh Ambani, who’s acquisition of Network18 Group gave him control over 70 media outlets with a reach over at least 800 million Indians (Kay and Palepu, 2024). The rise of sensationalism aims to both gain massive profits from viewership and distract the public from a variety of issues ranging from destruction of environment, failure of policies, or scandals of politicians and capitalists alike. While this helps populists as coherent debate on their policies and politics is limited, our own government with an aim to create a majoritarian-Hindu state, gets added support from capitalist media’s sensationalism to create more polarisation.

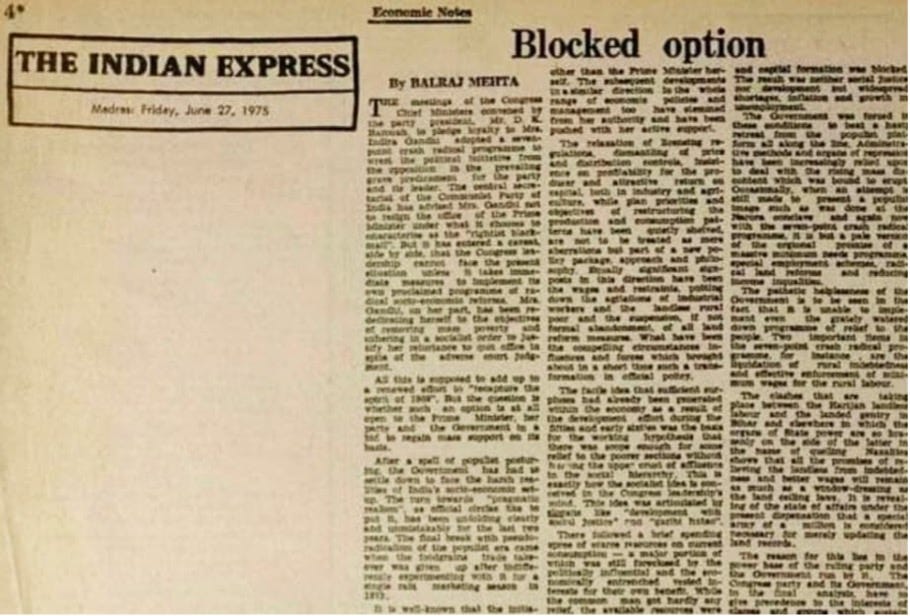

People’s uproar against attacks on freedom of press was sparked by the then-riotous media with newspapers like the Indian Express leaving blank columns in this newspaper as a silent protest. Following the emergency, constitutional protections for media were still not brought into law. Yet, there was an inclusion of this element into our social contract where the people of India now stood by its press, having learnt the lesson on freedom of press. The ownership and control of media by billionaire interests and the dominance of loud, brash, and angry TV presenters with their counterparts in political parties crowd out the space for coherent debate. This can suppress questions on the potential quid pro quo between massive conglomerates of these billionaires and the political parties.

The Indian media’s coverage of the recent Operation Sindoor was marred by misinformation where non-fact checked journalism instilled fear and anxiety among people. Such instances lead to people losing trust in the media and threatens this critical tenet of our social contract that formed in the post-emergency India.

Indian Express Newspaper’s Blank Column on 27th June, 1975. Source: Indian Express

As knowledge dissemination proliferates beyond the timeslots on our television screens and printed newspapers, misinformation and disinformation are more widespread than ever before. The short-form content dominates this landscape with more than 50% of Indians relying on platforms like YouTube and WhatsApp, accounting for 54% and 48% respectively, with lower but significant numbers for Meta and X (Reuters, 2024). This has significantly grown the appetite for quick information which seldom translates into informed opinions, thus giving populists with their quirky one-liners and catchy rhetoric a platform like never before.

India’s cultural diversity, which I have grown up believing to be a mosaic of colourful patches that create a fuzzy blanket, is being weaponised through polarisation. Global evidence has shown that populists gain and hold onto power in polarised societies with larger ease (Kleinfeld, 2023). Party-led polarisation and propaganda through new and old media helps create immense loyalty among conservative groups as witnessed in case of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) deploying WeChat as the primary news source for Chinese nationals in the United States (Zhang, 2022). BJP’s conservative voter base coupled with affordable internet and large amount of media consumption is a fertile ground for deployment of same tactics in a new flavour. BJP’s very own IT cell works as a potent unit, capturing massive qualitative data on its voter base every day and disseminating content that keeps the fire of party loyalty burning bright. This campaigning, including through WhatsApp (Jaswal, 2024) is not just hidden and effective but also expensive.

The strongest of my reservations against the presence of Big Money in politics is on the lack of representation that upstarts coming from working class backgrounds without the financial backing would have within these massive party machineries. Furthermore, even if they do get a voice in these huge machineries, receive the party ticket to contest, win a hard-fought election campaign to become a representative after the party bankrolls those expensive campaigns – who comes first, the Party or the Constituency?

Our former Prime Minister, and the son of Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Mr. Rajiv Gandhi, believed the party should come first. With an intention to limit horse trading and party defections, the Anti-Defection Law passed by his government gave political parties sweeping powers to disqualify legislators when they did not toe the party line (Roy, 2022). This was the second crack in our social contract. None of the governments who have come after, including the one by BJP, INC or the Emergency’s staunch opposition, has even attempted to get rid of this undemocratic law. Today, in addition to political parties having the power of Big Money, also have protection of the Constitution against dissenting legislators who do not have the same kind of loyalty to their distinct local electorate as they do for their political parties.

India’s diversity also comes with unique challenges and distinctions across districts as well as demographics. Our founders adopted the parliamentary system to ensure that our democracy is of the demographics and not party ideologies. The top-down system that this law mandates severely limits the legislators’ ability to exercise their responsibility to appropriately represent their peoples’ needs on the floor of the Parliament as the already existing trade-off between party and electorate is quashed by the Party High Commands. Let’s take an example, the National Education Policy (NEP, 2020) does not do enough to formalise and reform the competitive exam coaching institutes. My district of Latur in Maharashtra is a disorganised and informal coaching institute hub for the Marathwada region. This was an opportunity for the then Member of Parliament (MP) for my district belonging to the BJP to raise this issue on the floor and introduce an amendment. However, this did not happen. Makes one wonder if there was a quid pro quo between the MP and the bulwarks of informal coaching space that delivers terrible outcomes for young people or it was the MP staying quiet for party’s sake while their electorates and the constituency continues to suffer.

Alright, so we have elected representatives that don’t care about us - what do Veto Players have to do anything with this? Hold your horses, we are yet to reach the chunk of the iceberg and now I realise that this essay may not even cover all of it today – rest for another day.

Rise of Federalism, Election Commission and Veto Players

The Election Commission of India (ECI) expressed serious reservations against EBS by filing an affidavit against the scheme in the SC, strengthening the petition filed by the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) (Supreme Court, 2019). ECI, while not an indirect veto player, stands out as an autonomous institution that has expanded its mandate to ensure integrity of state and national elections throughout the years. However, an extremely powerful executive, backed by the first single party Lok Sabha majority in three decades, steamrolled them all.

Despite institutional decay and capture in developing countries, the ECI emerges as a success story among electoral regulatory bodies in the world. It has provided successful oversight to 17 national and 370+ state elections between 1952 and 2024. The ECI has strategically expanded its mandate through political opportunism from rise of competitive state-level politics, and entrepreneurial bureaucrats. The ECI’s profile began to change in India’s post-liberalisation era following 1991. This evolution in mandate is a result of the periodic rise of partisan veto players through party fragmentation at the centre, and INC’s diminishing vote share and loss in multiple state-level elections (Ahuja, 2021).

India’s first two and a half decades as an independent nation, until 1977, were dominated by a single-party majority of the INC. The 18-month national emergency declared by the Indira Gandhi government ended with INC losing the 1977 general election, first ever national loss in their history. ECI gained the confidence of opposition parties and state governments who desperately wanted a neutral referee for elections after the emergency that saw a dismissal of fundamental rights, and subduing of state governments and the judiciary. While Indira Gandhi managed to claw back power following the fall of successive coalition governments, her assassination in 1984 followed by the assassination of her son, Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 fragmented the INC.

This era of party fragmentation coincided with the post-liberalisation age of the Indian political economy, institutionalising coalition politics both at the national and state level. Between 1989 and 2014, all eight union governments were coalition governments while the number of states with coalition governments went up from 4 in 1995 to 18 in 2006. This coincided with the post liberalisation era which saw a 20% (in US Dollar terms) spurt in the export growth in 1993/94 (Acharya, 2002). This shift in political and economic reality for India’s federal democratic system enabled the rise of multiple veto-players and the power dispersed among coalition partners and interest groups at the centre and in states.

Political entrepreneurship and subsequent opportunism displayed by the Chief Election Commissioners (CECs) over the years significantly helped the ECI maintain their autonomy and expand their mandate. These entrepreneurial endeavours were supported by the judiciary starting with Indira Gandhi’s judicial disqualification in 1975 that started the Emergency. The disqualification was a result of a complaint made to the judiciary for violation of the election Model Code of Conduct. Over the years, ECI has censured political parties for the violation of the Model Code and actively enforces it to ensure free and fair elections. Interviews of CECs conducted by Ahuja clearly showed that ECI views the judiciary as an important safeguard (Ahuja, 2018).

However, it is crucial to recognise the limited role of the Supreme Court’s veto through the power of judicial review. This limited role is logistical where they have limited capacity resulting in frequent delays, political where the executive pressure continues to grow by the day and constitutional as it should be to ensure the balance of our democratic institutions. Judicial review allows the court to strike down legislation they deem unconstitutional. The court empowers people as a veto player through Public Interest Litigation (PIL) which allows Indian citizens to trigger judicial review by petitioning the court to intervene on policy matters in public interest. This veto is constitutionally constrained as only a responsive measure to legislations that violate the fundamental rights. Mrs. Gandhi’s disqualification by the judiciary was only the start of emergency, the end was brought through the massive grassroots movement that she and her supporters did not expect and the leadership of our very own Lok Nayak.

In today’s setting, a single-majority government in India without any partisan veto players has both the agenda-setter as well as a veto player advantage, which it initially leveraged with EBS. The Court’s EBS decision is a significant judgement that helps our democracy survive in the presence of an expansive executive force. Linking political finance with people’s fundamental rights cements transparency and accountability as the central values of the electoral process (Justice Sanjiv, 2024). While the court reeled in Big Money through EBS that provided disproportionate resources to one political party, federalism is a necessity for India’s democracy to be vibrant and responsive to people.

Indian democracy returns to coalition politics in 2024 with an underwhelming BJP majority. This political change is amidst BJP’s manifesto goals for electoral reforms, most prominently One Nation One Election (ONOE), which would synchronise all elections in the country. As a party with strong beliefs in majoritarianism that have goals of vote and profit maximising for themselves and their donors, ONOE would provide better return on investment. Holding simultaneous elections risks undermining federalism by sidelining regional parties, centralising more power with political parties, limiting the rise of partisan veto players as well as grassroots leaders who fight and win elections without massive financial machinery. Simultaneous elections could also affect ECI’s mandate of monitoring the Model Code of Conduct and worsen their already lowering credibility as a neutral referee in elections. (Kumar, 2024)

SC’s catalytic use of limited veto power reinforces the utility of PIL for people to be stronger veto players. The democratic balance requires the constraints on the SC to be such that it is only a veto power of last resort. The tilt of this balance towards the judiciary is a gateway to judicialization and overreach, another risk to our social contract, that we must be cognizant of as well. To quote, our former and late Finance Minister, Mr. Arun Jaitley, “The Indian democracy cannot be a tyranny of the unelected and if the elected are undermined, democracy itself would be in danger”.

This requires an emergence, strength, and vigilance from partisan veto players represented by state parties and, more importantly coalition parties. Coalition politics across our federal democracy is not restricted by the Anti-Defection law to the same degree. These partisan veto players can also reform and represent peoples aptly in political institutions such as the Standing and Joint Parliamentary Committees and the Upper House of Parliament that can help recover from democratic backsliding of the last decade while future-proofing our democracy against single-party majorities. Let’s not forget that it was the 400+ government of Rajiv Gandhi that passed this undemocratic abomination in 1985. (Still behind Abki Bar 400 par?)

Where do we go from here?

"Hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies" - Andy Dufresne writes to Red in The Shawshank Redemption

I firmly believe that us as a society, nation and polity are still far away from descending into a new kind of emergency. While our social contract with politics is eroding rapidly, nobody has suspended our freedom of speech, movement, or assembly, yet. I belong to the camp of people that believe this will not happen in its entirety to the same degree as the emergency, especially having heard our Home Minister’s empathetic address on the eve of Sanvidhan Hatya Diwas (Day to remember Murder of Constitution).

Lok Nayak JP Narayan championed for self-governing institutions that would put power in the hands of the people. We need political parties across the country, and we have more than a 100 of those, to become more representative of the people and in that process become the guardians of democracy that protect us from personalities like Mrs. Gandhi in the future. This would mean more politics, but definitely better politics, provided we also eliminate the plague of Big and Dirty Money from it.

More politics requires more questions and one of the big ones is, why is the Big Money interested in Indian Polity? I believe that for our democracy to thrive, us as Indians must look beyond the direct channels of political finance as well as the benefits that the capitalists claim to have ethically received – it might be a decoy for all we know. Look around you, study the economy and society’s evolution, and test the strength of our institutions by demanding transparency. Are there certain Mergers and Acquisitions that have recently happened which are uncompetitive and will turn our economy into an oligopoly before it has even had an opportunity to be competitive? Who is getting the government contracts and what is the state of our Public Sector Companies beyond the share prices? What is happening in this sprawling country of ours that we could be distracted from? If there are cuts being delivered onto our democracy, we must know how much we have bled, from where and because of whom. A nation of 1.4 billion people cannot become an autocracy while hundreds of millions among us remain active watchdogs of our democracy and the social contract.

Examples like those of Zohran Mamdani, who fought against Big Money that dominated the New York City (NYC) Democratic Party mayoral primary in the United States and won, give me hope and learning. Big Money has been particularly against Mamdani due to his socialist policies that affect their capitalist undertakings in NYC. Having run on a completely grassroots-led campaign based on sound economic policies and an authentic appeal to people, he surged in popularity and defeated the governor of New York, contesting to be the mayoral candidate for the Democratic Party, with very little thanks to the party itself. In this age of impunity around the world and democratic backsliding that is rampant in a variety of ways, the biggest risk to our social contract is from the capitalists who support populists.

I believe that this link between Big Money and Democracy is the one that poses the biggest danger and fuels my great fear – a world where the amount of money you have determines if your voice affects policy or not. Let’s keep alive our hope and collectively work to restore our social contract by campaigning for and participating in politics, media, and policy that is not run by special interests but instead by the voice of the people.

References

Ahuja, Osternmann. The Election Commission of India: Guardian of Democracy. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51701-4_2

Ahuja, Osternmann. From Quiescent Bureaucracy to ‘Undocumented Wonder’: Explaining the Indian Election Commission’s Expanding Mandate. 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3131947

Shankar Acharya. Working Paper No. 139. India: Crisis, Reforms and Growth in the Nineties. Stanford University. 2002. https://kingcenter.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj16611/files/media/file/139wp_0.pdf

Freedom in the World 2024. Freedom House. 2024. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/FIW_2024_DigitalBooklet.pdf

Chang, E. C. C. Electoral Incentives and Budgetary Spending: Rethinking the Role of Political Institutions. The Journal of Politics, 70(4), 1086–1097. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381608081073

Bose, F. Parliament vs. Supreme court: a veto player framework of the Indian constitutional experiment in economic and civil rights. Const Polit Econ 21, 336–359. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-010-9088-2

Justice Sanjiv Khanna. Concurring Opinion on the Judgment over the Unconstitutionality of the Electoral Bond Scheme. 2024. Supreme Court Observer. 2021. A petition was lodged in the Supreme Court against this by the Association for Democratic Reforms. https://www.scobserver.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Electoral-Bonds-Writ-Petition-by-Association-for-Democratic-Reforms-ADR.pdf

Kumar. P. 2024. Debate | The Arguments Against 'One Nation, One Election' Are Unconvincing. The Wire. https://thewire.in/politics/debate-the-arguments-against-one-nation-one-election-are-unconvincing/?mid_related_new

Press Information Bureau (PIB). 2024. With General Elections 2024 underway, ECI is on track for the highest ever seizures of inducements recorded in the 75-year history of Lok Sabha elections in the country. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2017913

Bhaumik. Electoral Bonds SC Verdict: Why did the Supreme Court strike down the electoral bonds scheme? | Explained - The Hindu. 2024. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/why-did-the-supreme-court...ke-down-the-electoral-bonds-scheme-explained/article67848657.ece

Supreme Court. 2019. Counter Affidavit on behalf of the Election Commission of India in Writ Petition (C) No. 880 of 2017. Association for Democratic Reforms & Anr. Vs Union of India. https://adrindia.org/sites/default/files/Electoral_Bonds_ECI_Affidavit_dated_27thMarch2019_compressed.pdf

Vaishnav. Electoral Bonds: The Safeguards of Indian Democracy Are Crumbling. HuffPost India. 2024. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2019/11/electoral-bonds-the-safeguards-of-indian-democracy-are-crumbling?lang=en

Roy, Chakshu. The Anti-Defection Law That Does Not Aid Stability. India Forum. PRS Legislative Research. 2022. https://prsindia.org/articles-by-prs-team/the-anti-defection-law-that-does-not-aid-stability

Kay, C. Palepu, A. Billionaire press barons are squeezing media freedom in India. Deccan Herald. 2024. Read more at: https://www.deccanherald.com/india/billionaire-press-barons-are-squeezing-media-freedom-in-india-2909919.

Kleinfeld, R. How Does Business Fare Under Populism? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 2023. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/06/how-does-business-fare-under-populism?lang=en

Zhang, C. WeChatting American politics. WeChat and the Chinese Diaspora. 2022. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003154754-10/wechatting-american-politics-chi-zhang?context=ubx&refId=b73d453b-3424-468d-a803-ede5136e8a23

Jaswal, S. Inside the BJP’s WhatsApp Machine. Pulitzer Center. 2024. https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/inside-bjps-whatsapp-machine

Levitsky, S. Ziblatt, D. How Democracies Die. 2018.

Reuters Institute. 2024 Digital News Report. 2024. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2024/dnr-executive-summary